It all started with a Perry Mason TV episode. Doesn’t it always? I find I can only go to bed after midnight when I watch a MeTV Perry Mason show. I need that psychic joypop of watching someone breaking down on the witness stand or leaping to their feet in the gallery crying out, “Yes I killed him- and I’m glad I did!” What irritates me is that I own every season of that show on DVD but they are way too high up on the shelves to bother getting to, so I get my fix on MeTV.

The episode in question was The Case of the Spanish Cross, and it was about a troubled teen named Jimmy Morrow, with a criminal record, accused of stealing a wealthy jeweled cross, and later of murder. But it was the actor who played Jimmy- Richard Miles who intrigued me. There was something so sensitive and touching about his performance. The poor kid took care of his alcoholic mess of a father and the only person defending him is the wheelchair-bound wife of the murder victim. You could see why lawyer Mason (Raymond Burr) and his devoted secretary Della Street (Barbara Hale) became so protective of Jimmy. I immediately looked up Richard Miles on IMDb and was surprised to discover he was “Peter Miles” as a child star of such movies as The Red Pony (1949) and Quo Vadis (1951) and then left to become a teacher and writer. He wrote the screenplay for They Saved Hitler’s Brain (!!!!!) and several novels including That Cold Day in the Park, which was made into a movie by Robert Altman starring Sandy Dennis in 1969. He died of cancer in 2002 at age 64, and his obit mentioned his “partner” Brian Quarch, so it was cool to find out that he was gay. But I just had to find out more.

Richard Miles was born Gerald Perreau-Saissine in Tokyo. He was raised in L.A. and other members of his family became actors also, including sisters Gigi Perreau and Janine Perreau. He broke into movies at an early age, playing the (uncredited) son of Humphrey Bogart in Passage to Marseille (1944). Bogart plays a tail gunner for the Free French Air Squad during World War II. During his bombing raids, he drops letters in a weighted steel tube over his wife (Michelle Morgan) and son’s (Richard Miles) house in France. Miles has a sweet scene celebrating his 5th birthday and waiting for the sound of his father’s plane overhead (which never comes).

In Possessed (1945), Joan Crawford is found wandering the streets of L.A. in a comatose state. She is sent to a psychiatric hospital and flashes back to when she worked as a nurse for an extremely disturbed woman. That woman’s husband is played by Raymond Massey, and sweet, curly-haired Richard (as Gerald Perreau) plays his son Wyatt, who races Joan up the mansion stairs. I don’t care how little he is, it may not be wise to beat Joan in a race.

Heaven Only Knows (1947) is about the archangel Michael (Robert Cummings), who descends from heaven to the wild west to save the soul of Duke (Brian Donlevy), a saloon owner and tough guy. Richard Miles is sensational as the sickly little boy Speck, always carrying around his beloved dog and devoted to Duke, who he can see the good in. Duke even rescues Speck from a burning building. But it is clear he is not long for this world. “I don’t feel a bit tired anymore,” he says to Michael at the end as they ride that last stagecoach into the sky together.

Who Killed Doc Robbin? (1948) is a Hal Roach, Jr. production that’s an old-dark-house mystery mixed with a Little Rascals scenario as a bunch of kids investigate the secret passageways of a crumbling old mansion to find a firing mechanism that will help exonerate their beloved older friend Dan-the-fix-it-man from a murder rap. George Zucco plays the mysterious Doc Robbin and Virginia Grey his suspicious nurse. Richard Miles (as Gerald Perreau) plays Dudley, who wears glasses and affects a superior attitude with the other kids, even while being chased by a gorilla down the halls of the creepy house.

Hal Roach Jr. corralled the same moppets for an earlier film- Curley (1947), where a series of pranks against the new teacher backfires badly. Richard Miles again played Dudley, the egghead, whose trick pen ends up spraying ink in his own face. Hal Roach, Jr. didn’t have the rights to the Our Gang comedies by then and was hoping to have lightning strike twice with these kids. It did not. (And when you get to the two children offensively nicknamed “This & That” you’ll be glad it didn’t).

The Red Pony (1949) Based on a book by John Steinbeck (who also wrote the screenplay), this is a poignant tale of Tom (now known as Peter Miles), growing up in a rather cheerless ranch in Salinas Valley with a stern, hard-working mother (Myrna Loy) and disillusioned father (Shepperd Strudwick). He looks up to the ranch hand- Billy (Robert Mitchum), especially when he gets a beautiful little pony as a present and has to learn how to care for him. Filmed in sumptuous color, and beautifully directed by Lewis Milestone, the movie is a showcase for Miles, who is extraordinary. A later scene where Tom has to fight off some buzzards is really harrowing. But it’s his sincerity and natural quality as an actor that makes this story so evocative and heart-wrenching.

Roseanna McCoy (1949) There’s a lot of feudin’ and fussin’ in this ill-fated mess about the endless feud between the Hatfields and McCoys in the late 1800s. Farley Granger plays Johnse Hatfield, and in a Romeo & Juliet plot twist he falls for the sweet Roseanna McCoy (Joan Evans). Cathy O’Donnell was supposed to play Roseanna, reuniting her with Granger (They Live by Night). But her sudden marriage caused the studio to cast the inexperienced Joan Evans, who lied about her age and was actually 14 at the time of the filming. Richard Basehart has a blast playing the twisted Mounts Hatfield. He even shoots “Little Randall” McCoy (Peter Miles) during a gunfight at a store and uses the injured kid as a shield for his getaway. Miles even got to appear on screen with his actual sister Gigi Perreau. Nicholas Ray was brought in to replace director Irving Reis in hopes of salvaging this mess, but nothing could.

The Good Humor Man (1950) is a raucous, screwball comedy starring Jack Carson as Biff, a kind-hearted Good Humor man, romancing Margie (Lola Albright). He gets accidentally ensnared and implicated in a murder and robbery. Peter Miles plays Margie’s irascible little brother, the leader of the Captain Marvel fan club in town, who rounds up all the kids in the neighborhood at the end to bicycle to the local school where Biff and Margie are fighting off the bad guys. The whole finale where the kids are pelting the crooks with basketballs and pies is jolly, good fun.

One of Peter’s last films was the big budget epic and box office smash- Quo Vadis (1951). It was about a Roman soldier (Robert Taylor) in love with a Christian (Deborah Kerr) during the bloodthirsty reign of Nero (Peter Ustinov, having a field day as the petulant bad boy, playing his lyre while Rome burns). Peter Miles shows up about an hour into the movie as the sweet-face Christian boy Nazarius, who, during the fire of Rome, cries out, “My mother, a wall fell on her.” Walked out of the city to safety by the Apostle Peter, the Lord speaks through Nazarius, saying that Peter should return to Rome while the Christians are being fed to the lions. Peter returns only to be crucified upside down. Fortunately, Nazarius gets to ride off into the sunset with Robert Taylor and Deborah Kerr at the end. Supposedly Elizabeth Taylor and Sophia Loren have uncredited cameos. Good luck finding them.

After that Miles did a bunch of TV shows like The Lone Ranger; 77 Sunset Strip; Father Knows Best; and that Perry Mason episode I saw him in. His longest running gig was on The Betty Hutton Show, Betty played a jocular, boisterous, manicurist named Goldie who inherits executive and legal guardianship of a wealthy financer’s three children after he dies. It’s a “fish-out-of-water” premise with Peter Miles playing the older, spoiled son Nicky, who snottily makes fun of Goldie behind her back saying she looks like an “iodine bottle.” Scheduled against the popular Donna Reed Show, it only lasted 30 episodes before it was cancelled. Shortly afterwards Miles left the business and went back to school. He also turned to screenwriting.

Okay, now we get to They Saved Hitler’s Brain. It’s actually two films, the first was Madmen of Mandoras, which was directed by David Bradley, the Chicago-born director who worked for a while at MGM, making Julius Caesar with Charlton Heston, who was a former college-mate, and the intriguing Talk About A Stranger starring Nancy Davis (eventually changing that to Reagan). Madmen was also shot by the great cinematographer Stanley Cortez (The Night of the Hunter). It’s about a scientist who creates a deadly nerve gas and is kidnapped and whisked away to Mandoras where a group of Nazis have kept Hitler’s head alive and plan to take over the globe (again). Scenes with Hitler’s head sneering in the back seat of a car have kept audiences howling for years. It’s a laughably dumb, but barely was released. Years later almost 20 minutes were added to the film to pad it for TV. Director Bradley was an Associate Professor who taught film appreciation at UCLA and rumors were the students cobbled together the extra scenes. They’re easy to spot because the male cast has slightly longer hair. This is when Peter Miles changed his name to Richard Miles, especially for this film’s script credit. How and why Miles came to write the screenplay for this bomb I’ve never been able to find out. Because he went to UCLA might be the connection. Who knows? But come on…wouldn’t you want to be on IMDb for having something to do with They Saved Hitler’s Brain?

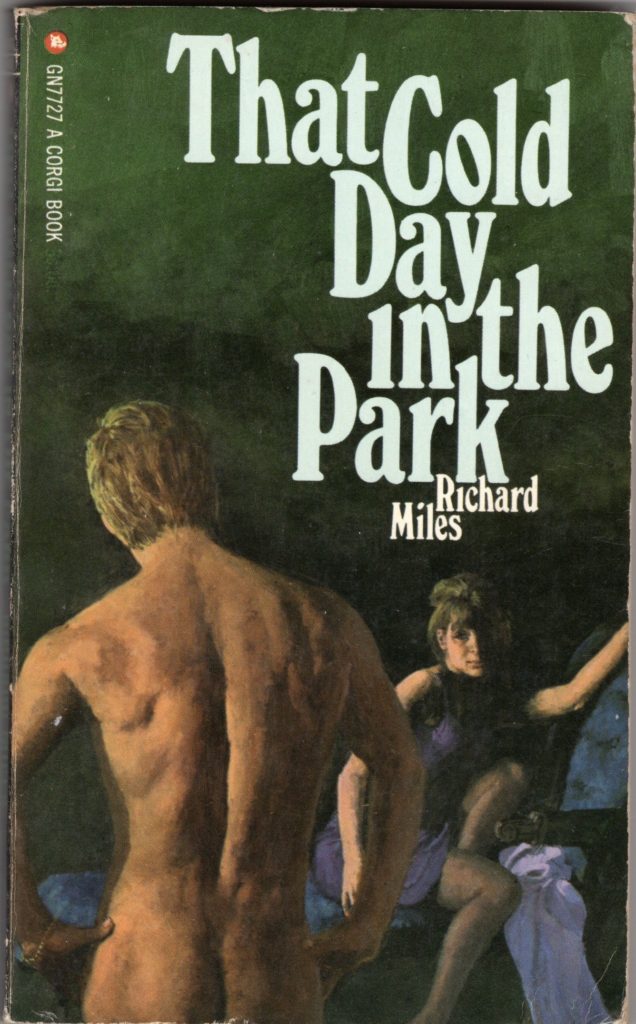

Richard Miles also went into teaching. He taught at the Burbank Jordan Junior High School (which became Jordan Middle School) and eventually Richard became president of the Burbank Teachers Association. He entered a writing contest at Dell Books with a novel- That Cold Day in the Park. He didn’t win, but Dell thought enough of the book to publish it. It’s a bizarre psychological thriller set in Paris, where the wealthy, lonely Madame, while walking through the Tuileries Garden in the rain, discovers a beautiful blonde young man sitting on a park bench, drenched and wearing a tee shirt. She tries talking to him and surmises he is mute and then coaxes him back to her lavish apartment. There she keeps him. Turning off her phone service and plotting how to make him content. But the boy, who is not a mute and is named Mignon, slips out the window at night and returns to his (possible) lover Yves. They are both male prostitutes and Yves goads him on about how much they could possible get robbing Madame and encourages him to go back and make a floor map of her apartment. But unfortunately, she discovers that he is escaping at night. Mignon returns, and while he is taking a bath Madame nails his bedroom window shut, imprisoning him in the apartment, determined to possess him completely. It’s a wonderfully sinister book- the writing is diamond-sharp and the psychological insights into these damaged souls are extraordinary.

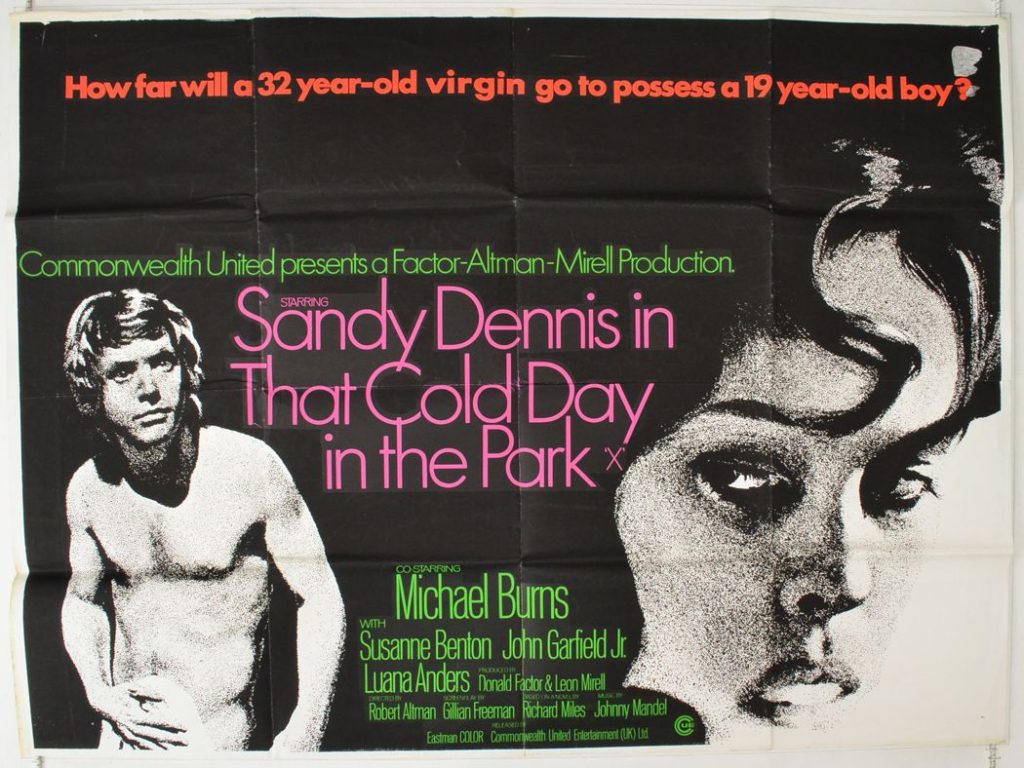

Now, the movie, directed by Robert Altman and starring Sandy Dennis and Michael Burns as the young man, is not set in Paris, and the gay angle is gone too- he slips out at night to see a girlfriend. In Pauline Kael’s dismissive review of the 1969 film she praised the screenplay by Gillian Freeman; the cinematography by Laszlo Kovacs and direction by Robert Altman, a filmmaker she came to champion. “But does anybody want to see a movie about a desperately lonely spinster (Sandy Dennis) who traps a young man (Michael Burns) and walls him up in her home?” She went on, “One can admire this film for its craftsmanship; it has a cold brilliance. But that’s all.” I disagree, but admit the novel has even more of a sad, sardonic punch at the end than the movie does.

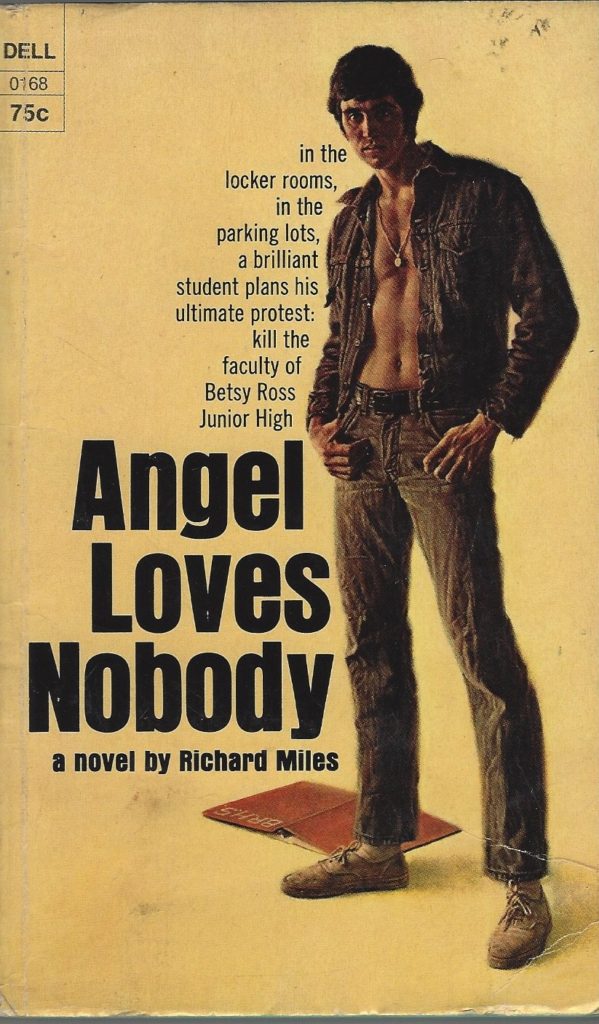

Samuel Goldwyn and his wife personally awarded Miles the second Goldwyn Writing Award for Angel Loves Nobody (1967). The novel concerns the new art teacher Tim Nielson at Betsy Ross Junior High. Classes are made up of a mix of white, Mexican and black kids, but one of his students- Angel Martine – disturbs him. On the surface this handsome boy is smart and charismatic, but something about him really unnerves Tim. And, boy, he’s right to be creeped out. Angel has assembled a crew of kids into his personal army. They meet in the third-floor boy’s room where they hang up a “closed” sign. He makes Colonels and Lieutenants of boys who can steal the master keys from the janitor’s locker or collect weapons. He carries a little black book in which he compiles a list that is all part of the “Plan.” He is building towards “D-Day” when he and his posse will lock down the school and begin executing teachers on his list. The art teacher uncovers the deadly plot but no one believes him. Will he be too late to stop “Zero Hour”? This kind of scenario was unheard of in 1967. It would be decades before a series of school shootings in this country would numb our senses to this horror. The book tensely hurtles along to the final nerve-wracking chapters. It’s a smart, savage thriller, but also a prescient glimpse into the rage and shared madness that teens are scarily capable of.

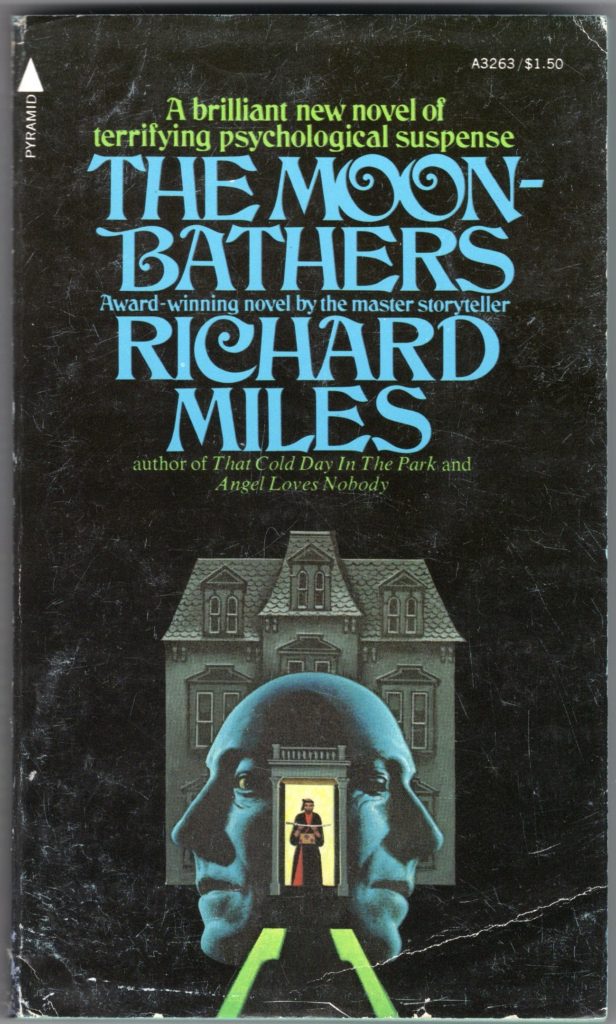

The Moon-Bathers (1974) is about a secret Japanese society, created after World War II called the Kinkakuji, named after the temple in Kyoto. Men met in cellars to rage that there are no American war criminals. So, they compiled lists of targets that they intend to eliminate 20 years later. Members take a blood oath, and a small, rotund businessman Hideo Sugi is traveling to L.A. with the name of his target- Shelby Chandler. Shelby lives in a house completely decorated with Japanese furniture and artifacts; with cabinets filled with ancient swords and rare ceremonial robes. After the war, Chandler had been sent to Japan to hunt down war criminals of his own, and locate POW bodies. Needing an interpreter, he meets Shimizu, who introduces him to Hideo Sugi, and they have remained friends through the years. That’s how the secret society operates- everything has to look accidental. There is also a secret in Shelby’s past that has haunted him through the years. Meanwhile, his new tenants- Kathy and her artist brother Guy- have moved in next door and Kathy keeps popping over to Shelby’s house to use the phone or when she is threatened by her stalker ex-boyfriend. The story shuttles back and forth between Sugi’s reluctance to fulfill his blood oath and the messy relationship between Kathy and the clearly disturbed Shelby. There is a strangely evocative section in the book where Shelby wanders through the sleazy section of the city, past the seedy bars; tattoo parlors and a movie theater showing Hot Time in Sin Town, where he meets up with a sailor who takes Chandler to a nearby gym to watch him box. It’s the damnedest book, seeped in Japanese culture in many respects, but really a character study of a very damaged soul.

Richard Miles died of cancer August 3, 2002 in Los Angeles, California, but his radical writing lives on in three amazing works of fiction that have haunted my sleep for the last few months. Thank you, Perry Mason.