Legendary cult British director Michael Reeves was only 25 when he died of an accidental barbiturate overdose, and, in his brief career, directed only three movies. But at the time of his death he seemed on the cusp of a great career. In describing his final film The Witchfinder General– Time Out Film Guide called it, “one of the most personal and mature statements in the history of British cinema.”

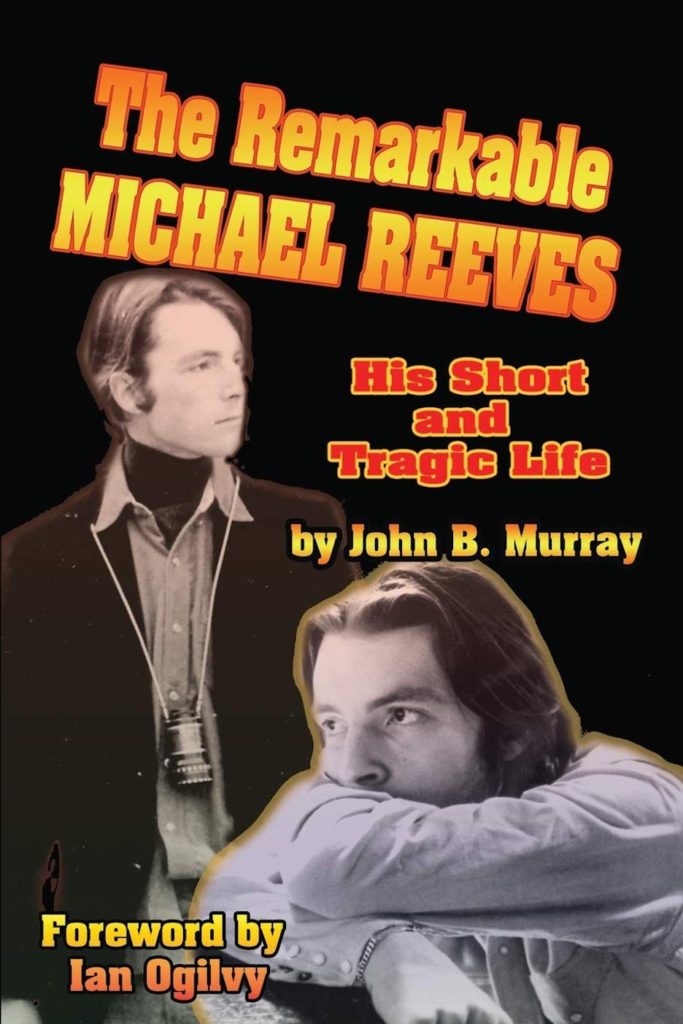

I just finished a great book about the director- The Remarkable Michael Reeves: His Short and Tragic Life by John B. Murray. It’s definitely the final word on the subject, and it made me go back and revisit his films and sadly consider what might have been.

Reeves grew up in affluent circumstances. He attended prep and middle schools and, aside from suffering the sudden and mysterious death of his father when he was eight, was an energetic, intelligent young man with an obsession about movies. Supposedly his mother took him to see the film Ivanhoe and afterwards Michael announced, “when I grow up I want to be Ivanhoe.” His mother laughed and said “You can’t be that, dear, that’s Robert Taylor.” So, he said, “Well I want to be the person who tells Robert Taylor what to do.”

As a young man, Reeves was obsessed with films and their makers, especially director Roger Corman and his favorite auteur- Don Siegel, who he began a lenghty correspondence with. Mike’s favorite movie was Siegel’s The Killers, based on the Hemingway story and starring Lee Marvin, John Cassavetes and Angie Dickenson. One of the more fortuitous meetings was when a friend introduced him to future actor Ian Ogilvy (who would appear in all of Reeves films) at a coffee house in Kensington when they were 15. Reeves was attending school at Radley and Ogilvy Eton, and the two became fast friends. They even collaborated on short 8mm and 16mm films that Reeves shot. When Michael Reeves was 16 something happened that drastically altered his life- for the better. He came into a large sum of money from his father’s side of the family which made it possible for him to live comfortably for the rest of his life.

So, what did he do after school finished? He hopped a plane for Hollywood and showed up at the front door of director Don Siegel and said “I’ve come all the way from England to see you, Mr. Siegel, because you are the greatest film director in the world.” Surprisingly, Don Siegel invited him in and later when Siegel was suffering a fever and was supposed to shoot some screen tests for producer Hall Wallis on Elvis Presley’s Fun in Alcapulco, he brought Reeves along as his dialogue director. Their friendship was “enhanced by a shared fondness for poker and cigars.”

Reeves returned to London and got a job on The Long Ships as a film-set runner but left before the film was finished because “he fell in love with the girl who would eventually live with him, Annabelle Webb.”

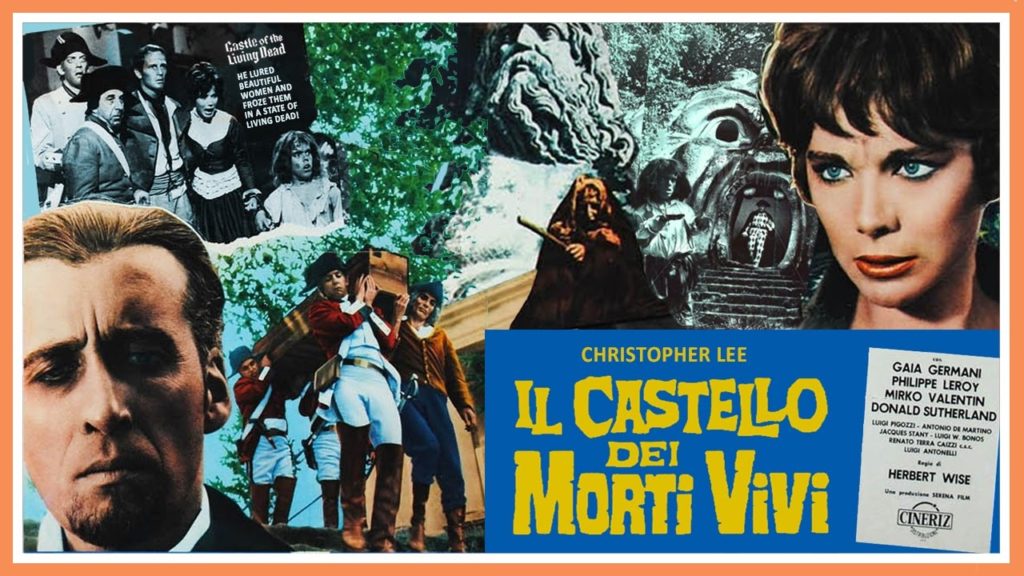

Producer Paul Malansky invited Michael over to Rome to help him punch up the script for a horror movie he was making called Castle of the Living Dead, a forgettable gothic chiller starring Christopher Lee and a very young Donald Sutherland. Christopher Lee and Reeves did not particularly hit it off, but later Lee was to say about him, “He had incredible enthusiasm and imagination, loved movies, knew all about them and was very eager and full of energy.”

Reeves worked on the epic Genghis Khan in Yugoslavia. After that he returned to Italy which was “experiencing a phenomenal boom in film production.” He used his own money as financing and came to producer Paul Malansky and said, “Look, I’ve got a script. I wanna make a horror film.” This became La Sorella di Satana , released as Revenge of the Blood Beast in the UK and The She Beast in the States. The film did “remarkably well considering its modest origins.”

The She Beast (1966), Reeves’ first feature, took three weeks to shoot in Italy starring the reigning queen of horror at the time- Barbara Steele (Black Sunday). It reunited him with close friend Ian Ogilvy who co-stars with Steele as a honeymooning couple in Transylvania who come under the spell of an ancient witch (a pizza-faced gorgon), who has cursed the town many years earlier. Mel Welles (Little Shop of Horrors) stars as a peeping tom hotel owner, and John Karlsen stars as the great grandson of Professor Van Helsing, who lives in a cave, and helps exorcise the vengeful witch. There are perverse flashes of humor, mostly at the expense of communism (a hammer and cycle gag is a riot). The saucer-eyed, dark-haired beauty Barbara Steele supposedly was given a flat fee of $5,000 for three-days-work but there was no stipulation on how long a day they could work her and she ended up exhausted and annoyed at the long hours she put in making the film. Although she recalled that Michael Reeves was a very enthusiastic young director.

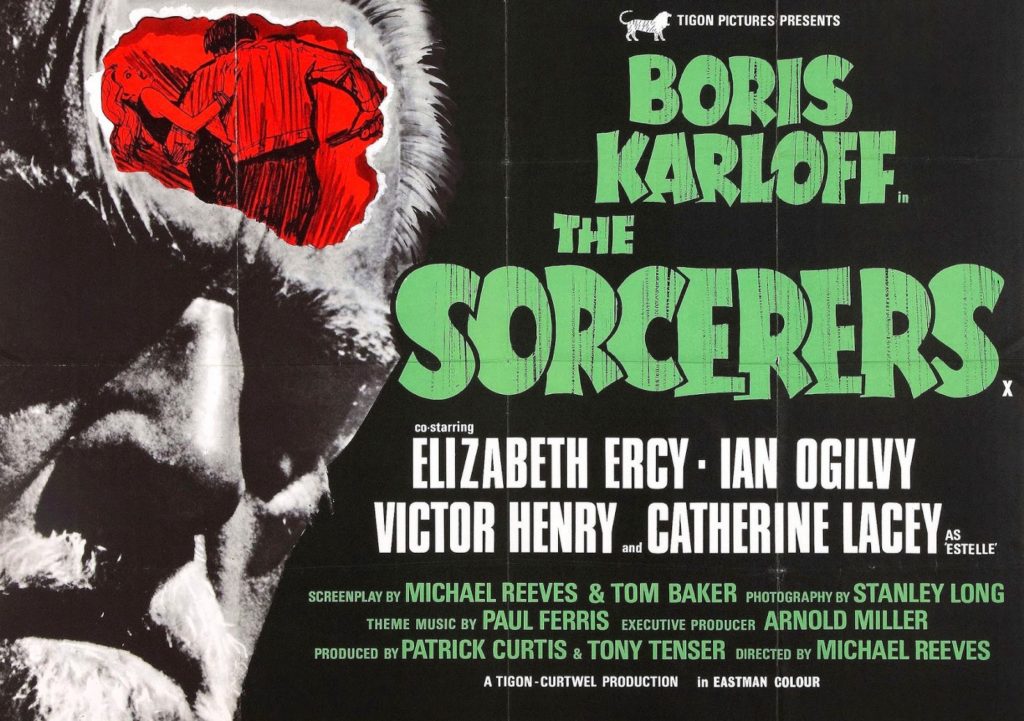

Michael Reeves second film The Sorcerers (1967) came about after he read a sci-fi story by John Burke called Terror for Kicks. He came up with a spin-off of that idea (with Tom Baker as co-writer) and they fashioned a perverse tale of an aging scientist Dr. Marcus Monserrat (played by venerable horror great Boris Karloff), who has created a machine that can let he and his wife Estelle (Catherine Lacey/The Lady Vanishes) vicariously experience everything their subject experiences. The Doctor goes out looking for “a boy who’s bored- looking for something” and runs into brooding Mike (Ian Ogilvy), who works at an antique store, and gets him to accompany him home. He straps Mike into his machine which flashes colored lights in his eyes and puts him into a hypnotic, fugue state. The elderly couple are able to control Mike’s mind through their thoughts and make him commit acts he has no memory of later on- like sneaking into a private hotel pool for a swim with his girl, committing a robbery, borrowing a motorcycle and speeding down the highway. Estelle gets wildly aroused after each session and, because her will is stronger than her husband, mentally commands Mike to commit acts of violence and even murder so she can experience it. A very young Susan George (she was 15 at the time) plays a hapless victim. It’s a very modern movie- not only in how it captures the swinging London scene at the time- but the twisted, voyeuristic scenario of this elderly couple vampirically getting off on the criminal sensations of the young man they control. The film was a happy shoot, and, according to producer Tony Tenser that had to do with “the cooperative temperament of its star Boris Karloff.” Boris even sent Mike a Christmas card which he pasted into his scrapbook which stated: “Here we are- Good Luck to us & heaven help us!” The film faced some difficulties with the British Board of Film Censors for the sadistic nature of the film but Reeves convinced the chief censor of his seriousness and the movie passed. It actually made a lot of money in America.

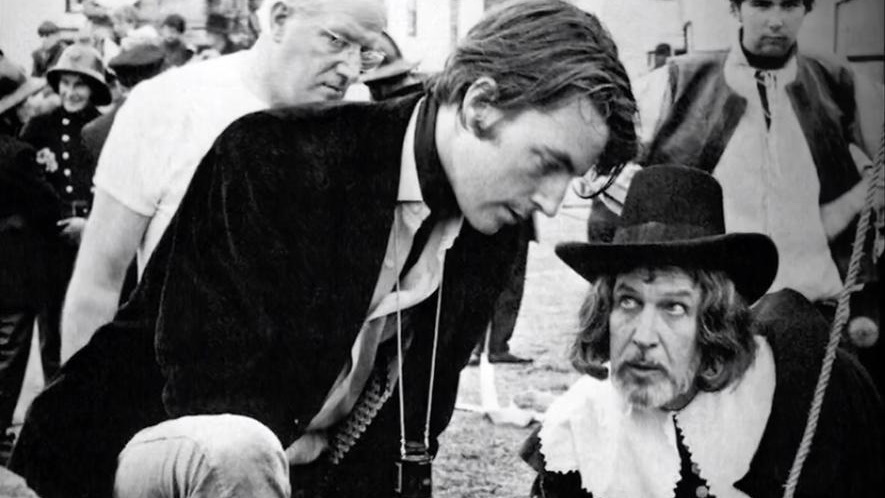

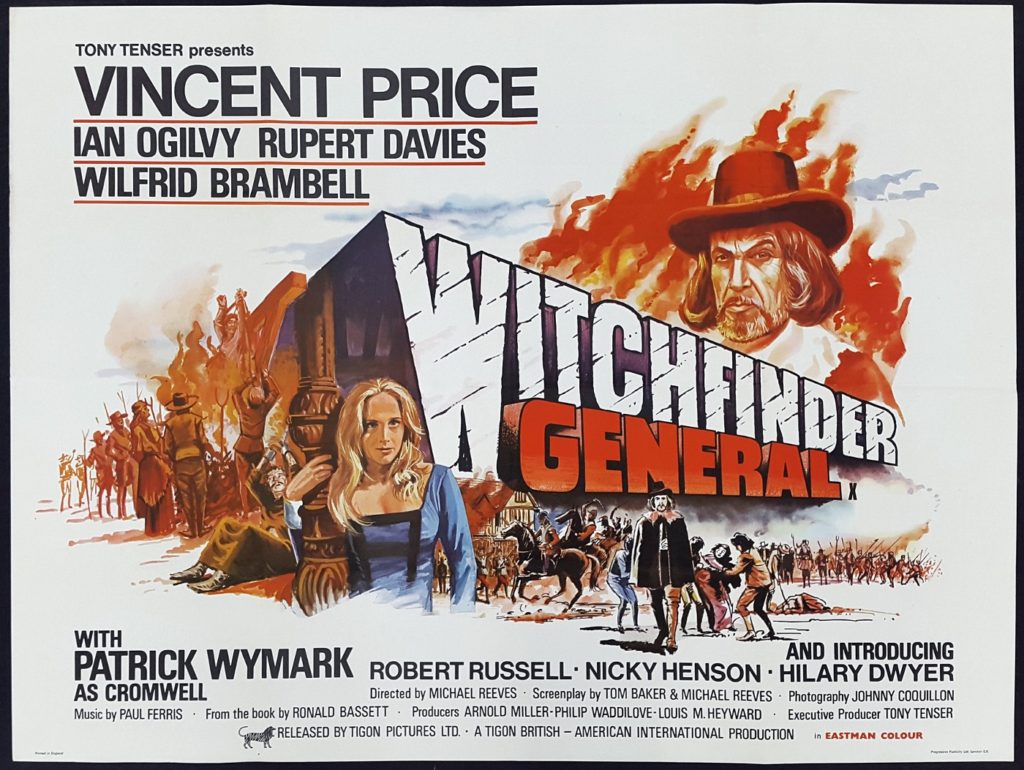

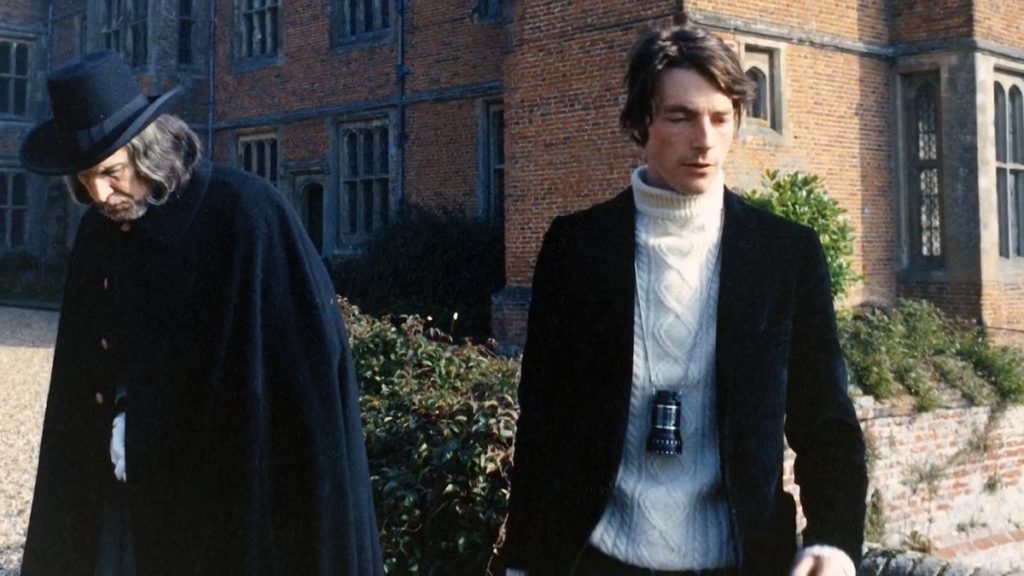

“I think violence and murder (in film) are quite justifiable,” said Michael Reeves in an interview in Penthouse. He was able to put this into practice in his next film- Witchfinder General (aka The Conqueror Worm) (1968), with a brilliantly malevolent performance by Vincent Price as sadistic rogue Matthew Hopkins, who roamed the English countryside in the 17th Century as the official witch finder. It was a stunning, violent, elegy of a film, and a glimpse of Reeves evolving into an astonishing director. Producer Tony Tenser snapped up an option on a book about the real Matthew Hopkins and came to Michael Reeves, who read it and flipped for it. Tenser contacted Sam Arkoff of American International Films to help with the financing. Reeves once again turned to Tom Baker to do the screenplay, and “the shocking violence of the film came from the research Tom did.” The location scouting was key and much of it was shot in Lavenham. Reeves had envisioned Donald Pleasence for the role of Matthew Hopkins but AIP ruled against it and was determined Vincent Price play the lead. Unwisely, when Reeves first met Price he confessed that Pleasence was his first choice for the role which, rightfully, put Vincent off. Vincent Price, by most accounts was the true professional. A witty, erudite man, art lover and gourmet chef. In fact, when the catering truck didn’t show up one day, Price “went into town, bought fresh vegetables, pasta and shrimp and prepared lunch for the cast and crew in the hotel kitchen.” But there was conflict on the set between Price and the director. Reeves didn’t want Price to fall into his old pattern of campy, oversized villains. He fought to bring out a real performance from Price and in the end, when Vincent saw the finished work, he agreed that Reeves was right. In an interview with David Del Valle in Video Watchdog, Price admitted: “Michael really didn’t know how to deal with actors. He got all our backs up. He’d come to you and say things that you should never tell an actor, things that give them no security at all. We didn’t get along at all, but I agreed with what he wanted. I think I understood what he wanted. I think it’s one of the best performances I’ve ever given, and I think it’s a classic picture of its kind.” Even Sam Arkoff agreed and said, “Michael Reeves brought out some elements in Vincent that hadn’t been seen in a long time. Vincent was more savage in that picture. Michael really brought out the balls in him.”

The film begins with a group of villagers dragging a poor wench accused of witchery to be beaten and hanged. The lushness of the background is in stark contrast with the shocking brutality of the mob’s actions, and this juxtaposition is key in Witchfinder General. The gorgeous cinematography of Johnny Coquillon and the lush score by Paul Ferris kept coming against the startling violence on the screen. The year is 1645 during the English Civil War and Witchfinder Matthew Hopkins (Price) roams the countryside on horseback with his sadistic henchman John Stearne (Robert Russell). They torture confessions out of suspected witches and get a tidy sum from the town fathers and move on. Richard Marshall (Ian Ogilvy) is a Roundtree soldier who uses a two-day leave to travel into Suffolk to see his lover Sara (Hilary Dwyer). Sara is niece to the village priest (Rupert Davies), who, after Marshall leaves, is falsely accused by townspeople of witchcraft and set on by Matthew Hopkins when he arrives in town. Tortured by having needles plunged into his back, Sara offers herself to Hopkins to save her uncle but he is called away and she is then raped by the brutish thug Stearne. Marshall returns and is horrified by what has happened and vows revenge on Hopkins and Stearne. Matthew Hopkins tries to frame Marshall and Sara for witchcraft but the tables are turned in one of the most savage and bloody finales, an ending that has haunted and disturbed me ever since I first saw it when I was 18.

The film caused a lot of controversy at the time of its release, particularly in London, where critics denounced it as, “repugnant” “persistently sadistic” and “morally rotten.” These vitriolic put-downs stung Reeves deeply. Also, the film was renamed The Conqueror Worm in America with tacked-on narration by Vincent Price at the beginning and end in order to lump it in with his Roger Corman– Edgar Allan Poe films. But the movie was a surprise sleeper hit for AIP. There were lines around theaters for the “really weird English film.”

The financial success of the film made it a problem for Michael Reeves as to what to follow it up with. There were talks about Shelly Stark’s When the Sleeper Wakes, and De Sade for AIP pictures, with a script by Richard Matheson (The Incredible Shrinking Man). During 1968 Michael Reeves’ depression grew. His breakup with girlfriend Annabelle haunted him. He eventually suffered a complete breakdown and checked into a private clinic in North London. Reeves was also considered for Bloody Mama starring Shelley Winters as the notorious gangster Ma Barker. It was something he initially was hot to do, and ironically, after his death his film hero Roger Corman ended up directing it. There was also The Oblong Box, another in the Poe-related films starring Vincent Price and Christopher Lee. But Reeves was in a downward spiral of prescription pills and manic depressive lows. Michael Reeves was found dead the morning of February 11, 1969 of a drug overdose. It was a shock to all his friends and family and rumors of his death by suicide only made things worse. Ian Ogilvy called his death, “the loss of a very close friend and I think quite a loss for the British industry.”

Re-watching his fascinating films again while I was writing this article only made me sadder at what Michael Reeves might have accomplished. One could easily imagine a point in time when a young man might have knocked on his door and said, “I have come all the way from American to see you, Mr. Reeves, because you are the greatest film director in the world.” It might have been me.