If ever there was a director who deserves critical reevaluation it’s the Czech-born Hugo Haas who wrote, produced, directed and starred in over a dozen movies in the 1950s. Very few are available on home video. In Leonard Maltin’s Movie & Video Guide his films are often rated “BOMB”. And the Film Dictionary writes off his work as: “dreary, low-budget melodramas usually focusing on an inevitably doomed encounter between a crude middle-aged man and a young temptress.” But after years of hunting down bootleg video copies I can’t tell you how much I’ve come to love Hugo Haas. His moody, character-driven tales of losers and lost souls are taut, well-directed, and endlessly fascinating.

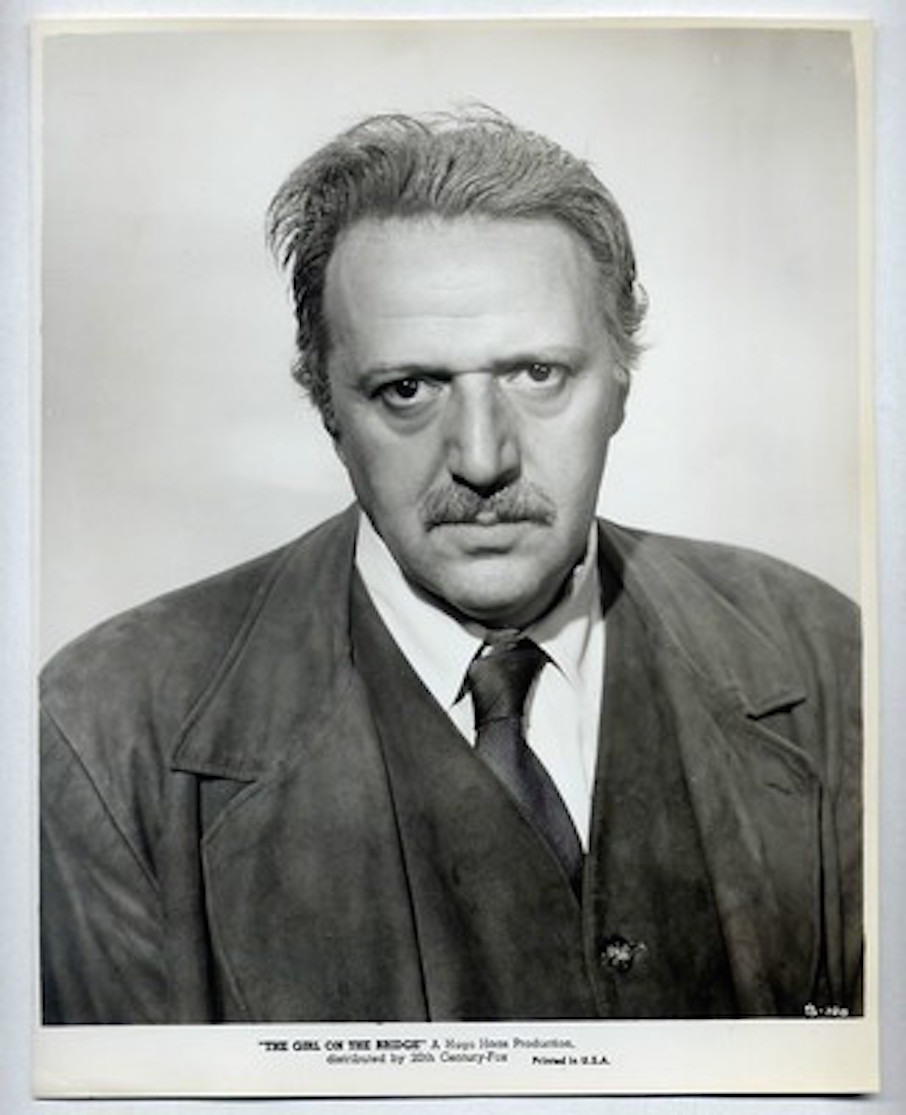

Haas, a celebrated actor and playwright in his native Czechoslovakia, was forced to flee with his family when Hitler invaded in the 1930s. He even made the top of the Gestapo’s “Most Wanted” list. Haas traveled to Paris and Lisbon before eventually coming to America where he became a well-known character actor in such films as A Bell For Adano, The Foxes Of Harrow and King Solomon’s Mines.

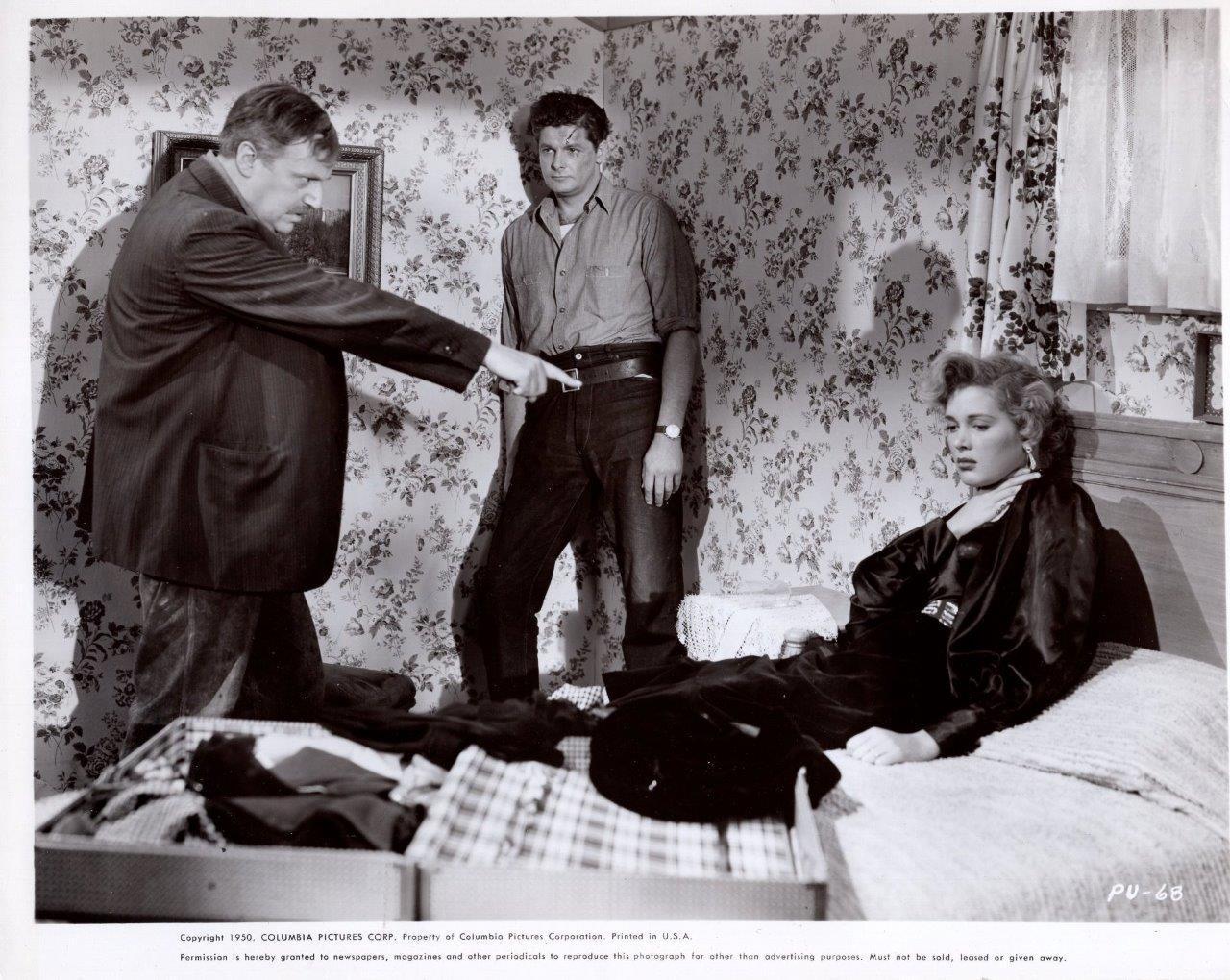

At age 50 Haas turned to directing with Pickup (1951), a tense drama of a lonely railroad man (played by Haas) who marries a devious, gum-chewing, dame (Beverly Michaels). He goes deaf but when his hearing returns he keeps it a secret after overhearing his wife and her boyfriend (Allan Nixon) plotting to kill him. Michaels is unforgettably nasty and as hard-boiled as a 15-minute egg. She also improvised much of her own dialogue. Haas admitted in an interview that he simply asked the actress “to use language she thought appropriate to the situation.”

An ironic twist ending is a staple in Haas’s films. In The Girl On The Bridge (1951), Haas played a kindly watchmaker who prevents an unwed mother (Beverly Michaels) from jumping off a bridge only to leap to his own death from the same spot. In Hit And Run (1957) Cleo Moore murders her husband, then discovers she actually killed his twin brother. Even Lucifer (Sir Cedric Hardwicke) gets the last laugh in Bait (1954) when a greedy prospector’s (Haas) scheme to cheat his partner out of a gold mine leaves him with a broken leg at his desolate mountain cabin and a killer snowstorm on the way.

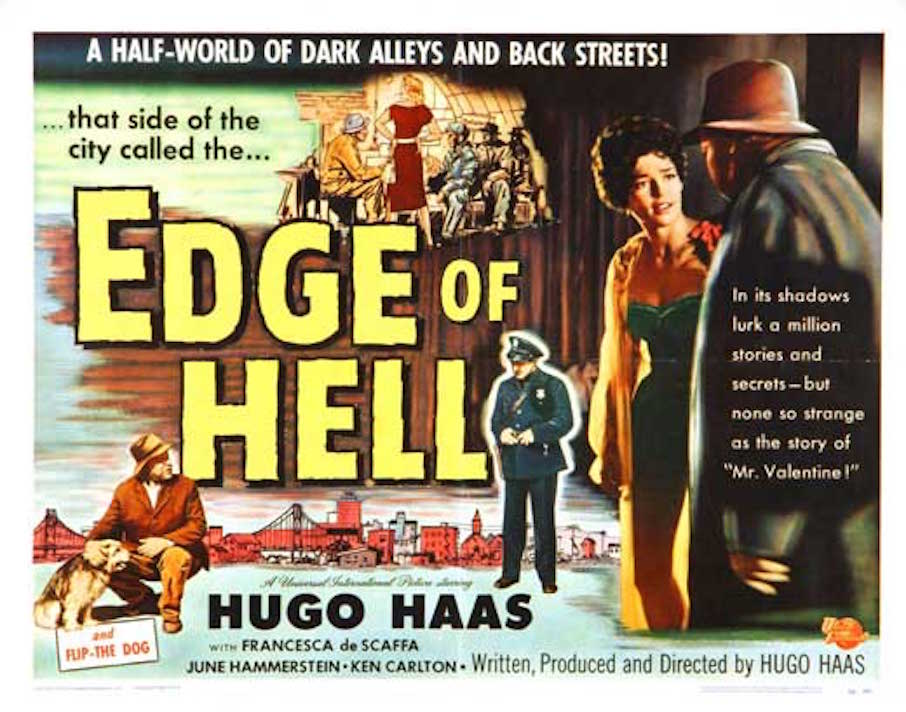

The most pitiful ending is in Edge Of Hell (1955), in which a beggar (Haas) sells his beloved trick dog to a rich family to insure it a better life, only to have the mutt die of a broken heart.

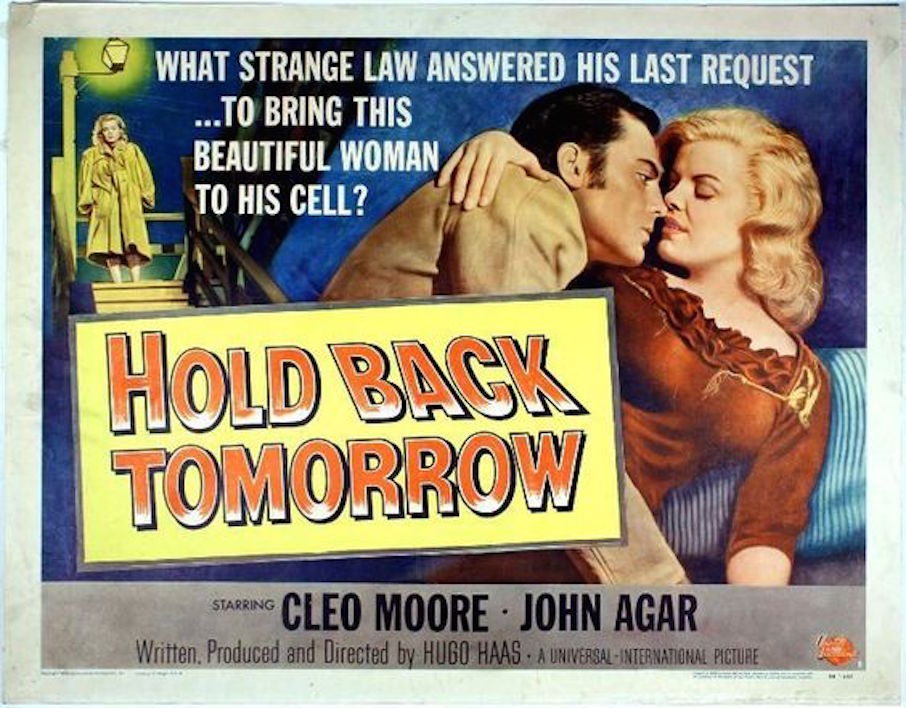

Statuesque blonde Cleo Moore replaced Michaels as Haas’s lead vixen, starring in seven of his movies. She was a blackmailing actress in The Other Woman (1954), a clever thief in One Girl’s Confession (1953), and a famous concert pianist’s wife who drives him to mangle his own hands for insurance money in Strange Fascination (1952). But her most interesting turn was in the bizarre Hold Back Tomorrow (1955) in which a death row inmate’s (John Agar) last wish is to spend his final night on earth with a suicidal prostitute (Moore). Onscreen Moore is a sexy log, but her wooden delivery is eerily effective here- she seems deadened and weary of life.

Her real life was much more colorful. At age 15 she was married for six weeks to the son of Senator Huey Long, the notorious Louisiana populist. She was famous for marathon kissing stunts and made headlines in 1955 by announcing on a televised talk show she would run for governor of Louisiana. She never carried out that threat, but the story was so often repeated that even her 1968 obituary stated that she had actually run for office.

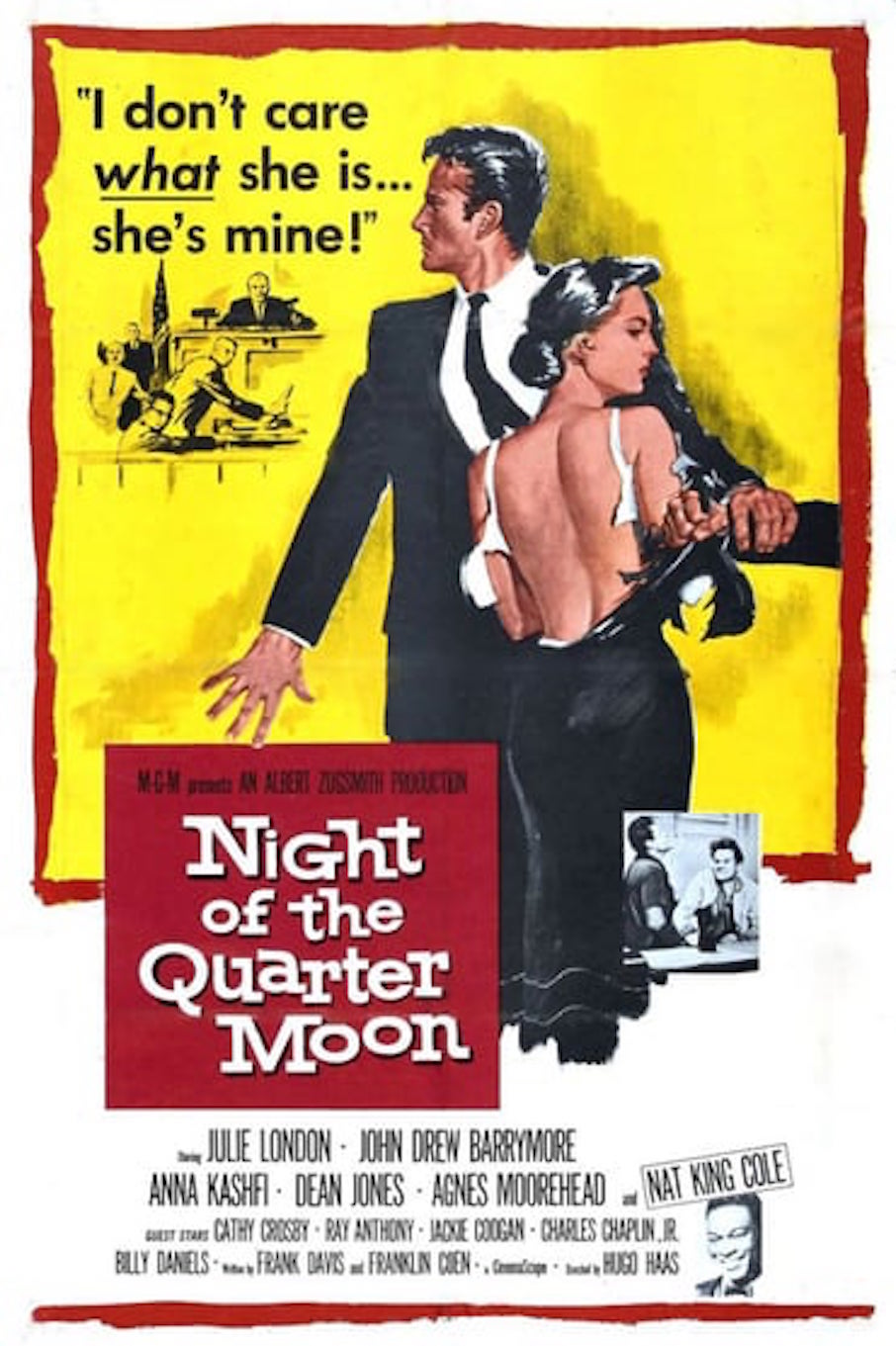

Haas tackled social issues in Night Of The Quarter Moon (1959) with John Drew Barrymoore as a Korean war veteran who marries a mulatto (sultry singer Julie London in dark makeup), making his San Francisco society mom (Agnes Moorehead) apoplectic. “Where did he propose to you- on a beach or in a cotton field?” Moorehead asks her new daughter-in-law. In a jaw-dropping finale London is forced to strip naked in a courtroom to reveal her skin color.

Eleanor Parker plays a woman tormented by three separate personalities in Lizzie (1957). Co-starring Richard Boone and Joan Blondell, the film was based on Shirley Jackson’s The Bird’s Nest. It might have been a hit for Haas if The Three Faces Of Eve with Joanne Woodward hadn’t been released the same year.

Paradise Alley (1962) starred Haas as an aging director who pretends to make a picture featuring the inhabitants of a seedy tenement but puts no film in the camera. His plan is to bring “love and harmony” to the acrimonious neighbors. Fittingly, this was Haas’s swan song in movies. This underrated director, who described his projects as “offbeat stories other studios would reject,” moved back to Europe and died in Vienna in 1968 of chronic asthma. Once asked what his greatest thrill from film production was, Haas replied: “Trying to make an A picture on a B budget. And,” he said with a smile, “to plan to make a feature in 10 days and actually finish it in 9 1/2 days- that is a real challenge!”

“I don’t care what she is – she’s mine!” Hysterical! I love it!