I was saddened by the death of Oscar-winning director William Friedkin, and pleased by the outpouring of sympathy by actors and other directors who recognized his genius. I met him on the set of To Live and Die in L.A. and he was unbelievably gracious to me. I’d heard stories that he could be scary when he wanted to be, but the Friedkin I interacted with was smart and kind and funny. The accolades all mentioned his most famous films The French Connection and The Exorcist but if you really respect a director it’s the lesser films that really reveal the filmmaker, and movies that were once considered flops- like Sorcerer– are finally rediscovered and recognized as the daring gems they are.

The one film of his that has haunted me ever since I first saw a screening of it is his 1987 film Rampage. The film had a troubled history. Caught up in the bankruptcy of the De Laurentis Entertainment Group the film sat on a shelf for five years. Miramax films finally freed it from its imprisonment and Friedkin had gone back and tinkered with it, altering the beginning and changing the ending. By then he had had a change of heart about the death penalty (which the film heavily addresses). And Friedkin was right- the original ending (which I saw from a European bootleg) just doesn’t work. The new finale is disturbing and gut-punching.

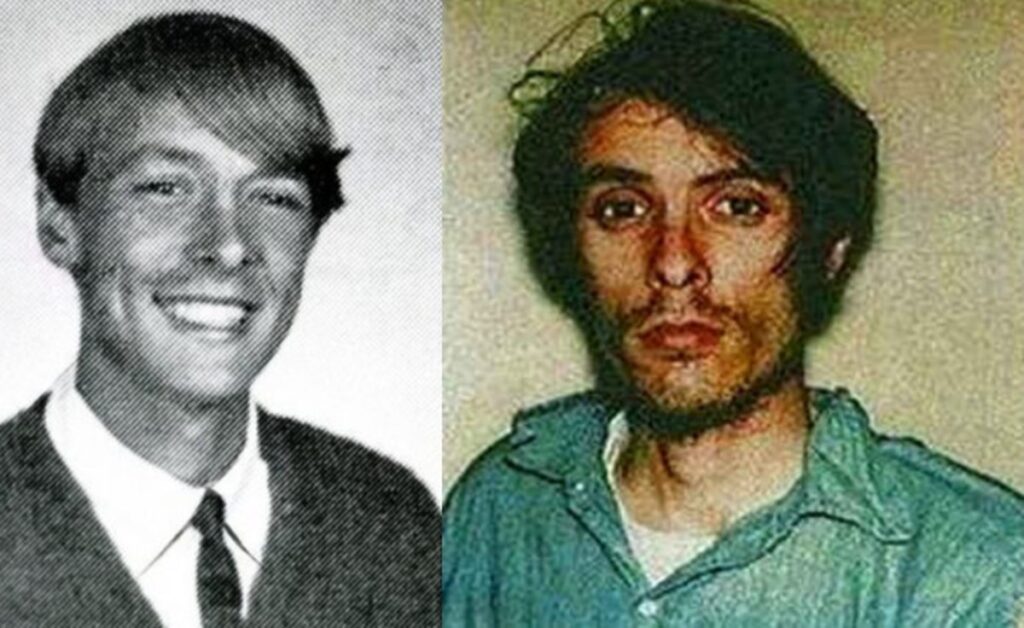

Based on the true story of Richard Chase, dubbed “The Vampire of Sacramento.” Rampage is the story of Charles Reece (Alex McArthur), an unassuming, good-looking young man with a psychotic compulsion to randomly enter suburban homes and shoot everyone in sight. Then he calmly mutilates the bodies and drinks the victim’s blood. Changing locations to Stockton, California, the movie follows Reece’s sporadic “rampages” to his subsequent arrest and trial for murder.

They sometimes stick closely to the true crime case, down to minute details- a bumper sticker on Reece’s car that reads “I’d rather be flying,” was also on Chase’s car. Police sent out an all-points bulletin looking for a straggly-haired young man in an orange parka, same as in the movie. Other details are changed for dramatic impact. The real Richard Chase spent time in mental institutions but was pulled out by his mother who was convinced he was well. In Rampage, Reece is released because of bureaucratic ineptitude.

It’s also the story of Anthony Fraser (Michael Biehn), a liberal D.A. who is forced to prosecute the killer, arguing in favor of the death penalty. And have the case prosecuted by a man tormented over the recent death of his daughter, as well as politically uncomfortable arguing against an insanity plea. While The Silence of the Lambs operates as a straightforward thriller and a movie like Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer uses a documentary-like approach from the killer’s point of view, Rampage reflects the broad impact that this deadly, peculiarly American phenomenon of serial killers has on our society- what it does to the victims, the attorneys, the jury and the families of the victims who are made to suffer in the process. In many ways it’s more frightening than The Silence of the Lambs and more emotionally resonant. You leave the film wiped out yet deeply moved.

William Friedkin truly was a great director. Aside from the successes of The French Connection and The Exorcist, what I loved about him was the way he delighted in transforming plays into films. From Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party; Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band; not to mention two by Tracy Letts– Bug and the ferocious Killer Joe. Anyone who ever worked with Friedkin had startling stories about how intense, volatile and perverse he could be on the set. For me, this only adds to the dark and interesting subtext simmering behind each frame of film. Rampage was made at the time Friedkin was going through an ugly, well-publicized custody battle over his son, and the sense of frustration, rage and loss permeating the film transforms it into an intensely personal movie.

Michael Biehn has never been better. Looking trim and handsome, he has the thankless task of spouting diatribes about the judicial system and victims’ rights over those of a murderer, which he handles with passion and grace. He never makes a wrong move on the screen. He is solid and right “there,” and you can’t help but empathize with his struggles throughout the grueling trial. Deborah Van Valkenburgh is radiant as his wife, and Royce D. Applegate, as the husband and father of some of the victims of Charles Reece’s handiwork is spectacular.

Alex McArthur makes a frightening killer. With his beautiful, angular face framed by long hair and his cold eyes staring out smugly during the trial, he creates an incongruous portrait of a murderer. He even causes one jurist to comment, “I can’t understand how a decent boy could change so much.” He is an enigma to everyone and Friedkin purposely reveals very little about him, aside from some allusions to a fucked-up family life. When they scan his brain in a hospital, a doctor states: “What it shows is a picture of madness,” but it is merely colors. One psychiatrist argues against the death penalty in order to study Charles Reece in the hopes of being able to stop other potential killers. But Reece says it best when he tells the police, “You’ll never know me.”

Friedkin shows restraint when it comes to the killings, but what he does show has chilling impact- a scene where Reece drags a victim to an upstairs bedroom is made all the more horrific when the camera cuts away to a child playing in a backyard, while in the distance Reece calmly lowers the blinds of the upstairs window. Sound is also skillfully layered and frightening- voices in the killer’s head mingle with the victim’s screams at alarming intervals. And Ennio Morricone’s score is haunting and evocative- seductive and nerve-racking at the same time.

Friedkin created an extraordinary film. I wish that someone would release a digitally restored version on Blu-ray- I think the last time it appeared on home video was Laser Disc. The film is beautifully directed with an ending that is all the more terrifying because it suggests that the horror continues, reaching out to damage its victims over and over and over again.